We did not purchase hull insurance for

Del Viento. Our boat will remain uninsured.

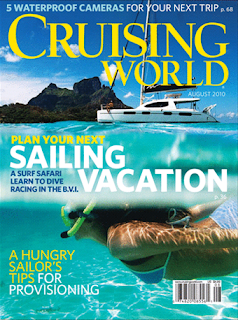

Photo by Adam Turinas

www.messingaboutinboats.typepad.com

We are fairly risk averse people. For example, while we have never owned a car worth enough to justify carrying collision insurance, we always carry a much higher level of liability insurance than legally mandated. We carry life insurance, we carry long-term disability insurance, and we have wills drafted and filed with an attorney.

So what the heck? Why are we leaving our second largest asset (after our home) sitting uninsured in Mexico...during hurricane season?! This object upon which all of our plans rest?

We often and increasingly resist making decisions on the basis of assumptions or expectations. Three examples: our decision to home birth, our decision to abandon the standard life raft model (more in a future post), our decision to ignore conventional wisdom with respect to investing.

While we never intended to carry hull insurance while living and cruising

Del Viento, we did intend to carry hull insurance for this year, until we could get down there and move aboard. Without thinking it through, we assumed the risk warranted the expense. So I looked into purchasing insurance, eventually receiving three solid quotes (each roughly $1,400 for the year). But I never committed. Instead, I set about further considering whether it was money well spent.

First, it was important to remember that no insurance company in the world can do anything to affect the likelihood of catastrophe befalling

Del Viento. Neither hurricanes nor failed thru-hull valves bother to check whether a vessel is insured before sending her to the bottom. While just the thought of

Del Viento sinking forces me to catch my breath, this anxiety should have no bearing on our decision whether to purchase insurance. Rather, we are considering only our strong desire not to bear the financial burden of her loss.

So how much risk are we assuming?

I think that the threat posed by adverse weather is very low. I learned all about the history of hurricanes and Puerto Vallarta. The last hurricane to come near the city was Hurricane Kenna in 2002. According to online historical references by cruisers, no boats were damaged and the top wind speed was 64 knots. There was a tidal surge in the marninas, but it was not disruptive. Category 1 Hurricane Lily came ashore near PV in 1971. Again, no damage to boats. Apparently, the city is regarded as a "hurricane hole" because it is geographically protected by Bandaras Bay and the mountains that form Cabo Corrientes to the north.

Additionally, our slip is way in the back of Marina Vallarta and behind a long stretch of two-story villas on Isla Iguana. It doesn't get any more protected from onshore winds than our spot.

I think the greater risk is a systems failure on board. A ruptured hose. A failed stainless steel clamp. A failed siphon preventer. Things degrade quickly in the marine environment, especially if neglected. Fortunately, systems redundancy decreases the likelihood that any single failure will be catastrophic. For example, hose clamps and bilge pumps are each backed up. Nonetheless, we are taking steps to decrease the risk that calamity strikes Del Viento:

- We hired a diver to maintain the bottom. Based on my conversations with our diver, he will report any indication that our bilge pump is running (indicating the boat is slowly sinking). Having worked as a diver for a few years, I know that this is something a diver notices.

- We hired the former owners of our boat as minders. They live nearby and are visiting and checking on Del Viento (still with the Dream Catcher name) at least once per month. Having lived and cruised aboard, these folks know the boat and her indiosyncracies better than anyone. Contrasted with any other boat minder we could have hired, they are less likely to introduce some human error that could increase the likelihood of fire or sinking. Among other things, they are operating her valves and checking her drains.

- Two separate liveaboards in nearby slips are aware we are absentee owners and are keeping their eyes open. One has our minders' contact information, and the other has ours.

- We are confident that our surveyor was knowledgeable and thorough and mindful of the fact that we will be away from the boat. He suggested one preventative measure: install a clamp directly behind the PSS shaft seal to prevent the stainless steel rotor from moving. Done.

The old girl has been floating since 1978. All of our plans would be upset if she stopped floating in the next 11 months. But we think the likelihood of this is so small that it does not warrant spending 2.2% of the vessel purchase price to pass the risk on to someone else. We are keeping that premium and self-insuring.

-- MR